In November 2012, the rebel movement M23 routed the best of the Congolese army and took the strategic eastern city of Goma. The army retreated to the nearby town of Minova. Over the following ten days, Congolese soldiers went on a rampage, looting much of the town and reportedly raping over 100 women and 33 girls, as well as committing other atrocities. The military hierarchy eventually handed over 39 army personnel, including seven senior officers, for trial on charges of crimes against humanity and war crimes.

In May 2014, the military tribunal passed its verdict: only two of the 39 accused were found guilty of rape, and one of murder. Some soldiers were found guilty of lesser charges. The other defendants - including all the officers - were acquitted. The verdict sparked national and international protest.

The Rape of Minova highlights the fundamental challenges to security sector reform (SSR) in the Democratic Republic of Congo. First, despite the capitulation of M23 in November 2013, general insecurity extends across vast swathes of the country – not just in Kivu where international attention is focused. Armed groups are rife everywhere. Second, the army is, at best, a poorly trained and ill-disciplined force, where soldiers often lack basic equipment and the rank and file may go hungry and unpaid. It is simply not able to defend the whole territory. Third, the army is often as feared by civilians as the armed groups, with justification – as the terrible events in Minova demonstrate. Finally, the police and justice sectors are seemingly incapable of installing and upholding the rule of law.

The Congolese case underlines the importance of treating the security system as whole, as promoted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC), rather than attempting to isolate different sectors. Increasing public safety requires deep reform of the army, police, and judiciary, as well as the relationships between them. Limiting the army’s role to protecting the territory, as per the Constitution of 2006, necessitates a functioning police service. An effective judicial system – military and civilian – is a prerequisite for ending human rights violations, including by security agents. This would be an extraordinary undertaking in any context, let alone one as vast and volatile as Congo.

These contextual constraints are exacerbated by structural challenges. After decades of kleptocratic dictatorship followed by an internationalized civil war, the way in which the army was recreated under the 2002 Global and All-Inclusive Accord is key. So too are the various security arrangements that came about from subsequent peace deals between the government and various armed groups. These agreements offered military positions and power to armed factions in return for disarmament (usually temporary). This type of power-sharing arguably provides substantial incentives for further ‘rebellions’ (meted out against civilians, not the state) and makes SSR extremely difficult.

With each new deal, ‘rebels’ are integrated into the army with no vetting of their competence, human rights records, or loyalties. Men with unsavory human rights records hold senior positions. The ranks are swelled with men with little or no training, many of whom predate on civilians. Centralized command and control remains elusive and the commission of serious crimes, including sexual violence, is routine.

For SSR programmes, there is a real risk that training the military and police in the absence of adequate discipline may help these men become even more abusive. Military justice carries little authority, as demonstrated by the Minova verdict. The ‘integration’ of new elements also means a constantly shifting and ever-increasing body of men to deal with. Establishing who is (and who is not) a member of the armed forces and police has become increasingly important.

Like the army, the police service created by the Global Accord comprises a mix of the ‘law enforcement’ forces from the belligerent groups, former police, and gendarmes. Some of these received training under the Mobutu regime, but not in democratic policing. There is still no policy or academy for police training, for example, so donors are limited to ‘non-essential’ training or training particular units in specific skills (related to elections, or investigating sexual violence). As with the army, the underlying challenge to police reform is poor governance but this issue remains unaddressed.

The justice sector – both civilian and military – continues to be a high priority for donors and activists. The challenge is huge: insecurity and isolation mean that justice institutions are simply absent from vast parts of the country. In response, the UN force have set up temporary courts in villages, with the provision of security and the judicial apparatus (judges, lawyers, clerks) to try specific cases. These mobile courts have brought some justice for victims of sexual violence, but only in the east. Nationally, however, and even in the cities, reform is slow and seems blocked by political interference, corruption, and incompetence.

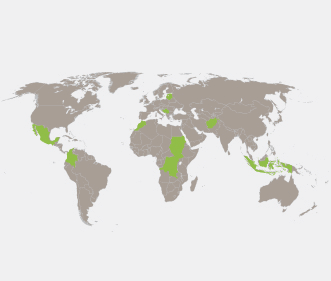

A range of international actors, including the UN and bilateral donors like the European Union (EU), United States, Canada, Great Britain, Belgium, and France, contribute to SSR across a range of different sectors, while African partners like Angola and South Africa, as well as China focus on defence reform. Among these donors, a fundamental conceptual rift exists between ‘reformers,’ who at least on paper promote SSR in line with the OECD-DAC principles, and more traditional ‘train and equippers.’

‘Reformers’ like the UN, Europeans, and North Americans support projects designed to improve the management capacities of the different security sectors, including through professionalizing personnel management, for example. Even among this group, however, little real cohesion and cooperation exists beyond sharing information. There is no common strategy regarding the missions of the different security actors, the values they (should) uphold and adhere to, and the democratic governance of the system itself.

Beyond improving the army’s ability to defeat armed groups, Congo’s government has shown little sign of committing to the type of root-and-branch reform needed across the security sector. Parliament and civil society do not generally participate in or monitor SSR, so the level of national ownership is low.

Reform-minded international actors and national civil society complain of a lack of ‘political will’ from the government for reform. The government does indeed resist a systemic approach to SSR and is particularly wary of foreign interference in the defence sector.

Critics of the government could do better however in understanding the reasons for this resistance. States are well known to be sensitive when it comes to defence cooperation, perhaps exemplified by the EU’s slow development of a common security and defence policy. Yet, when it comes to SSR in Congo, donors and analysts alike seem surprised that the government of an unaligned country resists allowing foreign powers access to its security service. Strategies that acknowledge this as a genuine constraint and seek to gain a better understanding of the obstacles to reform from the Congolese side might be more successful.

The contextual, structural, and political challenges to SSR point to the perils of euphemism. Peace and sustainable development in Congo require a security system that protects public safety. This does not require ‘reform’ of the existing system, but the creation of the new system – one described in the Constitution as a republican force at the service of the people as a whole, which protects the people and their goods. This is a monumental task, requiring robust political engagement by the government and donors. To date, ‘reform’ has been treated as a largely technical exercise addressing skills and equipment rather than mission and values. This is perhaps why there has been so little progress, as the citizens of Minova found to their cost.

Laura Davis is a researcher and consultant who specializes in justice for human rights violations in peace processes. Her publications include EU foreign policy, transitional justice and mediation: Principles, policy and practice (Routledge, June 2014). You can follow her on Twitter @LaDaBel.

Tags: armed groups, Global and All-Inclusive Accord, M23, OECD-DAC, Police Reform, SSR

Visit the Centre for

Visit the Centre for