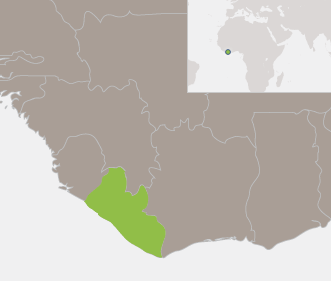

SSR Resource Centre Blog Contributor Gavin Raymond is a SSR consultant specializing in West and Central Africa. He examines justice and security reform in Liberia, and the corresponding lessons for second-generation SSR.

Liberia’s programmatic roll-out of five regional Justice and Security hubs, which seek to deconcentrate state justice and security (J&S) services nationally, is an underestimated initiative. The model’s capacity to provide clear, nationally accessible core public services outside the capital city presents an important possibility for the Liberian government to break from its past. Yet its strong potential may not be met despite the comparatively positive degree of political support from the UN and the government, as post-war reforms have focused too heavily on frameworks rather than actual change for Liberians.

The Liberian state is struggling to present itself as a relevant J&S provider to the majority of the population outside Monrovia, which has had consistently poor long-term experience with formal providers. Three factors currently constrain the model’s service delivery: wholly insufficient funding and resourcing, human capacity at all levels, and the dearth of infrastructure. Weak civilian oversight of the justice and security institutions since the state’s inception remains a major contributing factor. These long-term challenges are not unusual, but supporting agencies continue to address easier problems, an issue attributable to underlying dynamics within both the Liberia government and the UN.

The hubs are demonstrating potential to build state authority by improving protection from violence regionally. Early indications have shown encouraging results despite extremely low provider-to-citizen ratios, a weak penal chain and poor resourcing. They will be more likely to succeed if there is willingness to increase direct resourcing for formal providers, however, and to simultaneously improve coverage by co-opting informal actors. Strengthening of providers such as the Police Support Unit and Border Patrol Unit through provision of basic training, whilst clearly critical, has nonetheless continued to receive excess focus over mentoring and equipping them appropriately in their daily role.

The model also offers a significant opportunity to improve state legitimacy through a more efficient and accessible formal justice process and creation of relational openings between the state and communities, although it is clear that the ongoing failure of the justice reform process to create a genuinely impartial system is fundamentally undermining these successes. Popular conceptions of justice also heavily balance against a rights-based system. The model is capable of adapting to a more hybrid approach however, and this may offer one means for addressing this issue.

Liberia’s institutions are unlikely to be practically and independently held accountable to the population before the UN withdraws, an issue that threatens the strategic effectiveness of this model. UNMIL’s open mandate has permitted the UN to coordinate support for justice and security reforms, but an inadequately synchronised strategy has led to bureaucratic window-dressing on core issues such as the cross-cutting institutional susceptibility to elite manipulation. Current external support for the model appears to be intended primarily to enable a politically positive withdrawal for UNMIL, predicated by a decade of stability, disinclination to return to war and the balanced cost of the mission. Yet this overlooks the real risk in removing Liberia’s primary independent security provider having only superficially addressed one of its most significant long-term conflict catalysts.

It is clear that the hub model’s real success will not be quantifiable for some time. Its effectiveness remains heavily reliant on UNMIL’s presence, and on sourcing enough funding to develop effective, sustained coverage. It is reasonably likely, given the limited external benefit for the key influencers to address either aspect, that the programme may only achieve limited coverage and quality of service. This will increase its vulnerability to the significant internal risks from public disorder and elite manipulation. The model would be better placed to co-opt informal providers in each region to support the hubs, promoting local solutions through appropriately delegated responsibility.

Globally, legitimately human-centric SSR initiatives have been elusive, and second-generation SSR remains challenged by isomorphic and contextually weak processes. Designers and implementers of any related initiative need to focus on two equally important strategic aspects for success. They must plan in objectively human-centric terms that recognize more hybrid and multilayer approaches as a transitional path to long-term service provision. Building stakeholder commitment must also be a central feature, including detailing how the programme will actively engage reticent donors or political actors. A dual approach in this vein would recognize the method’s integrity and strong potential whilst enabling it to succeed despite the constraints of political reality.

Tags: justice reform, Liberia, SSR

Visit the Centre for

Visit the Centre for