Following the overthrow of Gaddafi, Libya’s new government confronted a steadily declining political and security situation. In Benghazi, where the 2011 revolution began, there has been an upward trend of violence. The capital Tripoli has seen armed men besieging government ministries and even storming Parliament. Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan was first kidnapped and more recently ousted from office, while his interim replacement Abdullah al-Thani only recently resigned following an armed attack against him and his family, exemplifying the sort of governmental instability that now plagues post-revolution Libya.

The government also has to contend with growing instability in a number of key regions. In the east, the Libyan state faces a unilaterally declared autonomous Cyrenaica government; a recent deal might have released some seized oil ports but the broader problem of how to deal with these eastern rebels remains. Meanwhile, Libya’s vast southern region remains largely ungovernable, marked by lawlessness and outbreaks of violence that the government appears unable to stymy. State control over trafficking and trade routes has only weakened, even when compared to Gaddafi’s heavily decentralized approach to the country’s periphery.

Border security is among the most important challenges facing the new Libyan government, even being the subject of an annual regional summit held in Tripoli in 2012, Rabat, Morocco in 2013, and expected to take place in Egypt this year. Of particular concern has been the illicit cross-border economy, which has long been a feature of Libya’s border communities but has taken on a new dimension with the post-revolution’s weapons trade

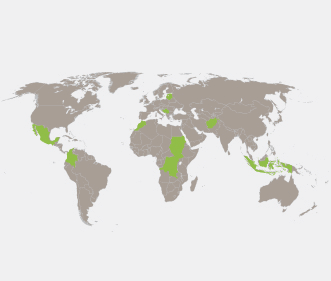

Much of the Gaddafi regime’s arsenal of weapons were looted from poorly protected arms depots, including heavy assault rifles, anti-aircraft guns, tank shells, and anti-personnel and anti-vehicle mines. These weapons have since found their way into neighbouring countries like Tunisia, Algeria, Niger, and even further afield like Syria. The instability generated by the weapons trade is perhaps most visible in Mali, where these arms underpinned a civil war from 2011-2012.This trade has had a deleterious impact on internal dynamics within Libya, where tribal militias and new revolutionary brigades have become better armed and more tied into the illicit border trade.

Aside from weapons, Libya remains a key transit point for hashish, heroin, and cocaine, with this burgeoning drug trade often conducted by “well-armed, organized, and violent gangs” that are key beneficiaries of the post-revolution weapons boom. Subsidized household goods, from fuel to sugar, continue to be smuggled across various points along the country’s 4,000 kilometer land border – owing to the government’s decision to continue subsidizing such materials, much like its predecessor.

Libya still has to contend with frequent migrant flows from sub-Saharan Africa. But this movement of people also brings some new dangers as well, not least when such migrants are either affiliated with terrorist groups like Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb or join ethnic compatriots to form insurgent groups, as took place in Mali when Libyan Tuaregs fleeing violence in their country helped form the Islamist National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad of North Mali.

Adding to these problems was Gaddafi’s legacy of a highly fragmented and poorly managed security apparatus, which had a dilapidated and rudimentary capacity for border control. The new government not only inherited this apparatus but also had to deal with revolutionary brigades and local militias, which took advantage of the revolution to expand their reach and capabilities. In many ways, they were aided in this effort by the government itself, which made the decision to place militiamen on the government payroll and rely on them to provide security.

For example, Libya’s borders are primarily secured by Border Guard and Naval Coast Guard forces. But it’s strongly suspected that these forces are either supported or are heavily made up of militias, whether armed groups nominally under the state’s authority (e.g., Libya Shield) or Tebu/Tuareg tribal militias along Libya’s periphery. Indeed, under Law No. 11, the National Transitional Council even registered and incorporated local militia forces into the Border Guard, creating a parallel management system for national and local forces along the border.

International donors clearly recognize the dangers posed by Libya’s poorly controlled and porous borders, as shown by their strong representation at the Tripoli and Rabat border security summits. They also made training Libya’s border security agencies a key pillar to their ongoing efforts at security sector reform (SSR).

At the forefront has been the European Union, which launched the EU Border Assistance Mission (EUBAM) in Libya, which is a 24-month civilian mission under the auspices of its Common Security and Defence Policy aimed to support capacity building in this area and establish an integrated border management strategy. Once fully operational, EUBAM will have a planned staff of over 100 personnel and an annual budget of €30 million.

Already, EUBAM Libya has helped to improve the capacity of Libyan Customs and Naval Coast Guard, with much of their work limited to Tripoli where the key training facilities for Libya’s border security agencies are located. Yet EUBAM Libya also reportedly plans on deploying field offices and undertaking field training outside the capital. Complementing this EU initiative are bilateral donor assistance from countries like Italy, which has played a crucial role assisting Libya secure its maritime/land borders through the provision of coastal naval vessels and radar technology.

Another hopeful sign is how Libya has moved to cooperate with its neighbours on border security. It has already signed bilateral border agreements with Algeria and Tunisia, a trilateral agreement with Chad and Sudan on surveillance, a military cooperation agreement with Egypt, as well as a multinational agreement with Chad, Nigeria, Algeria, and Sudan to establish a joint security committee to explore further areas of border cooperation.

Yet, despite these advances, Libya still has a long way to go before its border security situation stabilizes, let alone improves. The country’s borders are simply too long and sparsely populated, with cross-trade endemic to and heavily rooted in the communities along its periphery. Yet it’s also clearly a failure in Libya’s state capacity, in so far as political authorities in Tripoli have struggled since the revolution to provide security in urban areas and border communities alike. Without improved capacity, it’s highly unlikely that any regional border cooperation – often with countries that only possess a tenuous hold on their own borders – can really succeed.

It’s tempting to blame such problems on the legacy of the Gaddafi regime’s decentralized governance efforts. But Libya’s new government also bears its own responsibility for its current problems, given not only its abject failure to rein in the country’s burgeoning militias but attendant role in facilitating and indeed legitimizing such autonomous armed groups.

Libya’s challenge in securing its borders also points to a broader problem with its approach to SSR – the continuing role of tribal and revolutionary militia groups as both security providers and spoilers to national reconstruction efforts. At the very least, it should serve as a reminder on the need to effectively pursue DDR (disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration) of armed combatants, if one hopes to successfully reform and build up a state’s security sector capacity unhindered.

David McDonough is Manager, Research and Programs at the Centre for Security Governance, and a Research Fellow at Dalhousie University’s Centre for Foreign Policy Studies.

Tags: border security, DDR, Libya, SSR

Visit the Centre for

Visit the Centre for