Prevailing approaches to security sector reform (SSR) have tended to stress Westphalian notions of the state characterized by legal-rational norms and institutions. Thus, SSR processes have more often than not concentrated on the formal arrangements of the state and its security and justice institutions. Yet, such approaches are fundamentally at variance with the underlying realities of the African context, where many political and social transactions (not least in the security sector) take place in the context of informal norms and systems.

—-

This article is contribution #16 in our Academic Spotlight blog series that features recent research findings on security sector reform and security governance published in international relations academic journals.

This article is contribution #16 in our Academic Spotlight blog series that features recent research findings on security sector reform and security governance published in international relations academic journals.

This contribution summarizes research originally published here:

Niagale Bagayoko, Eboe Hutchful & Robin Luckham (2016) “Hybrid security governance in Africa: rethinking the foundations of security, justice and legitimate public authority”, Conflict, Security & Development, 16:1, 1-32.

As part of a partnership between the Conflict, Security & Development journal and the Centre for Security Governance, this journal article will be available free and open access through this link for a period of 6 months:

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14678802.2016.1136137

—-

Prevailing approaches to security sector reform (SSR) - and the associated policy literature - have tended to stress Westphalian notions of the state characterized by legal-rational norms and institutions. Thus, SSR processes have more often than not concentrated on the formal arrangements of the state and its security and justice institutions, focusing on tangible policy goals such as stronger mechanisms of civilian control, better budgetary management of security spending, training and professionalization, police and courts reforms, mechanisms of parliamentary accountability, or the provision of alternative livelihoods for ex-combatants. Yet, such approaches are fundamentally at variance with the underlying realities of the African context, where many political and social transactions (not least in the security sector) take place in the context of informal norms and systems.

This may well account for many of the limitations of efforts to reform the security sector and its governance systems. Although understanding and controlling the state dimension remains essential, the complexity of Africa as well as recent crises that have occurred in many African countries involving the security apparatus call inseparably for a deep understanding of societal realities, often informal, within which the security governance in Africa is rooted. Increasingly, references to the informal security and justice sector have crept into the SSR and ‘state-building’ toolkits, although so far based upon insufficient empirical understanding of how this sector actually functions in the political and security marketplace.

There is consequently a need to identify this complex amalgam of formal and informal networks, actors and norms which, alongside legally established structures, influence decision-making as well as policy implementation in the security sector and which together constitute what can be seen as “hybrid security orders”. By relying on the perspectives offered by sociology and anthropology in the daily functioning of security provision (both at the central and local levels), the analysis of hybrid security governance hopes to provide new and refreshing insights on networks and alliances as well as on competition, tensions, and conflicts within African defence and security services which may help to explain the difficulties in implementing SSR processes. It suggests that on the African continent, formal and informal systems tend to overlap, interrelate, and interpenetrate at complex levels and that states and informal networks are not mutually exclusive but should rather be seen as embedded in each other:

First, such an approach is likely to offer a key input to understanding how do informal norms, solidarities and networks become embedded in the official security, policing and justice institutions of fragile and conflict-affected states. Policy-making in these institutions do not necessarily follow bureaucratic rules or deliver according to their official mandates. Decisions tend to be influenced instead by prevailing power relations, by various forms of patronage, by the social networks in which they are immersed and by alternative norms and codes of behavior framed in the language of ‘custom’, ‘tradition’ or ‘religion’. Analysis of hybrid security orders can provide in particular a better knowledge of the socially embedded forms of reciprocity, which inform leadership, recruitment, promotion and social networks both in and beyond the security sector.

Second, the hybridity approach may help to investigate non-state actors whose influence compete against or to the contrary interface with and complete the intervention perimeter of state institutions and legal frameworks. There has been a recent flowering of interest in security and justice provision beyond the confines of the state. This stems in part from the perception that state security and justice institutions are failing in their core functions and lack legitimacy and public support. Yet we still have an incomplete understanding of how these non-state actors function. The starting point of an approach in terms of hybridity should be a mapping of the relevant actors and bodies in each national or local context. The issue at stake is not only to consider the claim that vigilante groups, militias, faith-based militants, customary authorities in some cases offer credible protection and are seen as legitimate by local communities; but also their wider impacts in eroding or reinforcing the state’s monopoly of legitimate violence.

Third, should be considered the impact of hybrid security orders on the security and entitlements of citizens in African states and in particular on vulnerable and excluded people and communities. There is a dire need to identify empirically which hybrid processes on the one hand foster inclusion and accountability; and which on the other hand reinforce exclusion and violence. The ambition should be to provide a better empirical understanding of how and for whom oversight mechanisms work in situations where parallel channels of influence and informal networks, non-codified norms and non-state actors actually determine the allocation of resources and security provision.

Finally, the bottom-line is to determine to what extend can effective, inclusive and accountable security, policing and justice be negotiated in contexts of hybridity and informality, and foster new forms of public authority better suited to the political, economic and social realities of African states, in particular in post-conflict environments. The concept of hybridity could potentially encourage rethinking of the entire basis of security provision. In addition to contributing to strengthening the research and evidence base of SSR, this approach might carry important policy implications for how we approach security governance in Africa. Analysis and policy have scarcely begun to touch upon the deep politics of reform or to draw in any systematic way upon the critical literatures on hybrid political orders and security. In this regard, the ultimate intent should go beyond the use of ‘hybridity’ as an analytical tool to inquire as to the extent to which the concept can provide the underpinnings of an approach to building more effective security and security governance systems.

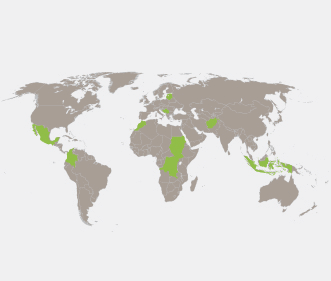

This article is part of a research programme on ‘Hybrid Security Governance in Africa’ funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) of Canada. Information about the research network may also be obtained by contacting the Programme Officer, Elom Khaunbiow at elom@africansecuritynetwork.

Notes on Contributors:

Niagalé Bagayoko has published widely on African security issues, taught at the Institut d’Études Politiques in Paris, been a Research Fellow at the IDS, Sussex, managed (2010–2015) the ‘Peacekeeping and Peacebuilding Programme’ at the International Organisation of La Francophonie (OIF) and is on the Executive Committee of the African Security Sector Network (ASSN).

Eboe Hutchful is Professor of African Studies at Wayne State University. He has published extensively on military politics, security sector governance and the politics of economic reform. He is Executive Secretary of ASSN and leads its ‘Hybrid Security Governance in Africa’ network funded by IDRC. He co-ordinated drafting of the AU’s Security Sector Reform Policy Framework and belongs to the UN Secretary-General’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters.

Robin Luckham is Emeritus Fellow of IDS, Sussex. He has held positions at universities in West Africa, USA, Australia and UK. Since writing a seminal book on the Nigerian military in 1971, he has published extensively on militarism, democracy, security governance and latterly ‘security in the vernacular’. He is also on ASSN’s Executive Committee.

Tags: Africa, hybridity, Security Governance, security sector reform

Visit the Centre for

Visit the Centre for