Hate speech and proffering war online using social media, particularly Facebook has contributed to South Sudan’s return to conflict. As Juba burns, the role of social media, online hate speech and rumor is becoming clear. As leaders call for ceasefire, calm and peace, internet warriors are beating the drums of war, some may even be partly responsible for sparking this recent escalation of violence. In a macabre way the internet has truly connected the world.

Fighting appears to have erupted between the guards of President Salva Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar just as South Sudan celebrated its fifth birthday. It quickly spread to other parts of the city and by Monday the 11th the fighting was reported in a number of towns.

This situation shows how precarious the politics of implementing peace agreements can be, and illustrates the challenges of the wider state building process in South Sudan. While the specific details of what transpired up to the initial shots being fired remains unclear, it is apparent that deep mistrust and paranoia have created the conditions where an unfounded rumor or accusation could trigger much larger conflagration.

Everyone in South Sudan is in active survival mode and there is a prerogative to act on whatever information is at hand. Many people believe the alternative is to risk their life and the survival of their communities. In this context, people are unwilling to take time to verify rumors or information passed on to them. This is most dangerous in the case of those charged with protecting the main political antagonists, President Salva Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar. For the men charged with defending these leaders the pressure to protect is great and there is an imperative upon them to act immediately when given news of danger to their respective patron.

The information war on social media

Added to the tension, paranoia and anger, is the fact that there are numerous individuals with clear agendas ranging from political machinations to hate. The internet and social media afford an avenue to express such views as well as to act on them.

As bodies were being counted on the 8th of July, from the fighting that began outside the Presidential headquarters, it became clear both the government and SPLM-IO (the former rebel forces integrated into government under power sharing terms of the peace agreement) spokespersons were making statements and direct interventions that were escalatory and fueling the violence.

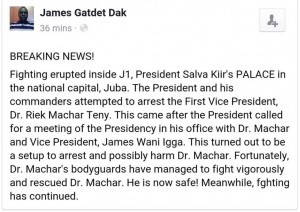

One example was how the SPLM-IO spokesperson, James Gadet Yak, commented that Riek Machar was to be arrested. One of his posts is reproduced here.

This was shared widely on Facebook. It spread rapidly, quickly collecting the additional story that Nuer were being hunted house to house, harkening to violence that lead to the war in 2013. The IO spokesperson has since apologized for this statement indicating that he had been misinformed. Unfortunately, the damage had been done.

The Dynamics of Hate Propaganda on Social Media

In the past - in South Sudan and other contexts - hate and direction of violence were spread using radio. Currently in South Sudan messages of hate are being spread via Facebook, Twitter and SMS. In this context, the role of those outside the country, notably the diaspora, has increased with the ability to communicate directly and quickly with these new tools to contacts and people throughout South Sudan, especially in the capital Juba. With social media being used prolifically by journalists (as sources and means of transmission) and a proliferation of commentators online claiming credibility, such messages quickly gain authority and visibility. Messages of hate and rumors are now often originating, or at least spread by those outside South Sudan. Various media outlets grant credibility to such rumors. People then spread the rumors and hate messages under the guise of open sharing of information. Combined with the paranoia and anger of a traumatized population, this new factor in the conflict dynamics of South Sudan, and in many other settings, is a recipe for disaster.

From Social Media to War: A South Sudan Security Dilemma

There is a palpable sense amongst many communities in the country that they must show strength and force or be marginalized, or even worse be eradicated. Many, especially those with a security responsibility, see the situation in stark security dilemmas. Societal tensions and cleavages in the security services, along with desperate economic crisis, have conspired to create all the requisite conditions of a relapse to war – all that was required was a spark, which the wrong rumor at the wrong time can trigger.

The mechanism is as follows. Many people in South Sudan especially youth, facing major difficulties in accessing information, are turning to Facebook as a primary source for news and information – and in many cases as their only source. They then pass this information on to others via very effective local word of mouth channels, given greater scope and velocity due to mobile phones. The comments particularly by those in the diaspora, but also many media and other commentators, are then filtered back through communities. Such sources, especially those with education in the West are seen as authoritative by many back in South Sudan. People then act on whatever information they have since they are in active survival mode and there are few opportunities for verification. The action taken is at best antagonism and at worst overt acts of violence. This dynamic also grants justification to many to act on sentiment or desire that might have been curtailed without a supporting narrative.

Moving forward: A ‘Countering Violent Extremism’ approach

What has clearly been missing from the mixture of interventions in South Sudan is the effort by concerned governments and international organizations to find ways to remove, or at least limit, the dangerous effects of hate and rumors bring transmitted, often from people located in other countries. While many governments have moved to deal with extremism online when it is connected with Islamist militant and extremist groups, the same has not been the case with extremism, hate, and proffering war in sub-Saharan African contexts like South Sudan. Canada for example has legislation about hate speech and has long been an advocate about the responsibility to prevent and protect but does little to intervene when people in Canada and/or Canadians have engaged in such hate and extremism online. There are similar situations in Australia, UK and the USA.

International organizations and others interested in peace and security in the region need to engage on the issue of the use of social media and communication of hate and violence, as part of the responsibility to prevent and in the context of countering violent extremism approaches. Existing tools to monitor and rapidly analyze communication online could have afforded potential for rapid response to contain fighting, to dispel rumors and to deny credibility to those instigating violence with fear. For example, had the UN Peacekeeping force in South Sudan been effectively using social media monitoring tools they might have anticipated this spark and been able to move forces to the right places in Juba to prevent, or at least curtail the spread of violence and help protect civilians.

At the time of writing a tenuous ceasefire was giving respite from the worst fighting, yet online the war of hate and propagation of rumor and conspiracy continues. In social media forums those calling for restraint and peace were being heckled and responded to with anger and the instigation of inter-communal war. Sadly, the war is raging both online and in the streets. While Salva Kiir, Riek Machar, and other leaders were calling for ceasefire, restraint, calm and peace, the internet warriors were busy tweeting and Facebooking hate.

Matthew LeRiche is a lecturer in international politics, conflict, security & development. He is an expert in political and conflict risk analysis, initially specialising in the political and security dynamics of South Sudan where he has worked since 2006. Whilst studying for a PhD at King’s College London, he undertook extensive field research in South Sudan and East Africa on humanitarianism and its impact on the conduct of war. While working in the field he was able to establish and develop relations with all levels of actors from local communities to high-level commanders of rebel armies and government. More recently, as Visiting Assistant Professor at Memorial University and Post-Doctoral Fellow at the London School of Economics, Matthew has been involved in research on the history of norms and war in Sudan, peacebuilding and East African security, among other topics. Furthermore, he has been engaged as a Security Sector Reform consultant and adviser on Defence education institutions.

Tags: CVE, Social Media, South Sudan, violence

Visit the Centre for

Visit the Centre for