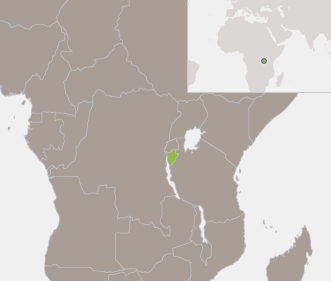

SSR Country Snapshot: Burundi

Note: This country profile, written before the 2015 Burundi protests, provides valuable background information on the security sector reform process in Burundi. If you notice any information that needs to be updated in this SSR Country Snapshot, please let us know at [email protected].

One of the most recent and insightful analysis on SSR in Burundi was written by Nicole Ball for the Clingendael Institute:

Burundi is a low income, transitional state under stress. Security sector reforms started in 2000.

-SSR Snapshot: Table of Contents

1. SSR Summary

2. Key Dates

3. Central SSR Programs/Activities

6. Major Civil Society Stakeholders

7. Key Domestic Government Actors

-

1. SSR Summary

Following independence in 1962, there was a gradual monopolization of the army (FAB) by Burundi’s Tutsi ethnic minority. This resulted in the domination of the country’s institutions and elite by Tutsi nationals and the violent repression of the majority Hutu civilian population. In June 1993, Hutu presidential candidate Melchior Ndadaye won Burundi’s first pluralistic election on a platform of reforming the security sector. These reforms threatened some privileged actors and triggered the assassination of President Ndadaye by elements of the army in October 1993, sparking a civil war that lasted until August 2000.

Two events can be associated with the beginning of the security sector reform (SSR) process in Burundi. The first is the 2000 signing of the Arusha Peace Agreement, which identified SSR as indispensable for a sustainable peace. The second is the August 2003 election of the National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD), which became the primary driver of SSR. The SSR process has focused mainly on the re-organization of the armed forces to ensure greater ethnic balance in the institution.

In addition, since 2005 Burundi has had a democratically elected government, representing the longest period in the country’s history that a democratic regime has held power. However, despite the tremendous progress that has been made, Burundi still faces significant challenges in establishing effective public institutions and dealing with the legacy of ethnically charged civil war. And while security on the ground has improved dramatically — especially since a cease-fire agreement was reached with the last remaining armed rebel group (the PALIPEHUTU-FNL) in 2006 — stability remains elusive in the country, creating a major challenge for reform.

-

2. Key Dates:

- Independence: 1 July 1962 (from UN trusteeship under Belgian administration)

- Signing of the Arusha Accords (2000), which lead to a power-sharing agreement and elections in 2005 and 2010.

- In February 2005, the new Constitution was approved with over 90 percent of the popular vote.

3. Central SSR Programs/Activities:

The UN Office in Burundi (BNUB), approved in 2010 and operationalized in 2011, replaced the UN Integrated Office in Burundi (set up in 2006 to assist efforts towards peace and stability after decades of ethnic fighting between Hutus and Tutsis) as a scaled down successor. The key functions of the BNUB are to support the Government in strengthening the independence, capacities and legal frameworks of key national institutions. In particular, the BNUB supports the judiciary and parliament, promotes dialogue between national actors, fights impunity and protects human rights. The Security Council gave BNUB an initial twelve month mandate ending in December of 2011, which was extended until February 15, 2013.

The Security Sector Development Prgramme (SSDP) was a three-year program (ending in 2011) between the Netherlands and Burundi focusing on the development of the Burundi security sector. The SSDP which targeted the Armed Forces and Police was conducted with the long term aim to improve the security of Burundi civilians through strengthening the legitimacy, effectiveness and quality of the Burundi security sector (DCAF-ISSAT).

Strengthening the capacities of police structures in Africa – Burundi (Phase 1: 2008- 2012/ Phase 2: 2013-2015 ), is a program carried out by the GIZ on behalf of the German Federal Foreign Office which seeks to strengthen the capacities of police structures in Africa. This program is active in several African countries, including Burundi. Its aim is to strengthen police forces and police institutions through the provision of training, infrastructure and equipment, while also developing management capacities (GIZ, 2013).

The ongoing World Bank/IDA Emergency Demobilization and Transitional Reintegration Project (EDTRP) was established to promote peace and security. The project demobilized 29,527 adult ex-combatants from 2004 to 2010 (World Bank, 2009).

In 2012 the government committed to the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to investigate and address past crimes, however, progress has been slow and marked by a lack of transparency. None the less, the Commission once functional has the potential to play a prominent role in Burundi’s reform process going forward.

4. Key Funding Commitments:

Returning refugees represent a major challenge for the Burundi state. UNHCR estimates in 2013 - 38,000 refugees and asylum seekers will be in need as assistance. For this, UNHCR has an operational budget (for 2013) of $25 million USD (UNHCR, 2013).

Administered by the World Bank, the Emergency Demobilization and Transitional Reintegration Project for Burundi, set to close in December 2013, has an operational budget of $22.5 million USD for DDR processes (World Bank, 2013).

Overall, Burundi is heavily dependent on bilateral and multilateral assistance, with foreign aid comprising upwards of 42% of the country’s national income (CIA, 2013).

5. Major International Donors:

- International Development Association (IDA)

- United States

- The Global Fund

- United Kingdom

- European Union

- Belgium

- African Development Fund

- Germany

- Netherlands

- Canada

Beginning in 2012, the United Kingdom through DFID cancelled all bi-lateral aid to Burundi and closed its office in Bujumbura. Including components pertaining to education and health, the aid also included provisions for improvements in the justice sector. In the year before the aid was cancelled, the UK through DFID contributed £13.7m to Burundi or nearly 4% of all incoming aid to the country (The Guardian, 2012).

6. Major Civil Society Stakeholders:

Réseau d’Actions Paisibles des Anciens Combattants pour le Développement Intégré de Tous au Burundi (RAPACODIBU): Started in 2008 by a group of ex-combatants in Burundi. The main focus of RAPACODIBU is on small arms control and DDR

The Training Centre for the Development of Ex-Combatants (CEDAC): Focuses on the reintegration of ex-combatants. CEDAC has been active in the socioeconomic reintegration of 25,000 ex-combatants and has received support from the UNDP and UNIFEM.

The Conflict Alert and Prevention Centre (CENAP): Founded in 2002, CENAP is a non-partisanNGO working on conflict resolution in Burundi. Through their research, they attempt to provide practical insights into potential catalysts for conflict and facilitate dialogue. CENAP has carried out projects on the ground and has correspondents across Burundi monitoring local conflicts.

7. Key Domestic Government Actors:

The new Burundi Constitution adopted in 2005, includes many provisions pertaining to the reformation and oversight of the Security Sector, and remains one of the core elements of Burundi’s overall SSR process.

Reform of the army was one of the key demands of Hutu rebels. Included in the peace agreement are provisions that ensure the army will not be dominated by one ethnic group, mandating that the army cannot be comprised of over 50 percent of Hutus or Tutsis.

Apart of ongoing reform, the Government of Burundi has established the Independent National Commission for Human Rights and the Institution of the Ombudsman as key parts of the consolidation and promotion of the rule of law and human rights in Burundi.

8. Central Challenges:

Refugees: The UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates in 2013 that 30,300 refugees and 8,000 asylum-seekers in Burundi will be in need of assistance (UNHCR, 2013). Furthermore, UNHCR estimates that there are upwards of 79,000 internally displaced persons in Burundi (UNHCR, 20113).

Justice/ Prison System: According to the International Centre for Prison Studies (ICPS), the estimated prison population of Burundi is 10,389 of which 62.6 percent are pre-trial detainees. With a total of 11 detention centers in the country with a total capacity of 4,050, the current occupancy level is at 256 percent over official capacity (ICPS, 2012).

Burundi National Police (BNP): In 2004, under the direction of the Government, Burundi brought together five different security organizations with the aim to create a single national police force (BNP) which is comprised of many ex-combatants. With a force size of approximately 17,000, the BNP is in need of downsizing and professionalization (GIZ 2013).

Impunity and ethnic tension: According to a Human Rights Watch report, ethnically charged and politically motivated killings are still widespread in Burundi. The report, You Will Not Have Peace While You Are Living: The Escalation of Political Violence in Burundi, documents political killings stemming from the 2010 elections in Burundi. These killings, which peaked toward the middle of 2011, often took the form of tit-for-tat attacks by members of the ruling National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (Conseil national pour la défense de la démocratie-Forces pour la défense de la démocratie, CNDD-FDD) and the opposition National Liberation Forces (Forces nationales de libération, FNL) (HRW, 2012). In the vast majority of cases, justice has been denied to families of the victims.

9. For More Information:

Multi-Annual Strategic Plan 2012-2015: A rolling document and review of the efforts of the Government of the Netherlands in Burundi. To date, the Netherlands remains one of the chief contributors to SSR in Burundi and this report provides excellent insight into the progress that has been made so far as well as current conditions on the ground.

Human Rights Watch (2012) “You Will Not Have Peace While You Are Living: The Escalation of Political Violence in Burundi”: An 81-page report which provides excellent background information and current analysis on ethnic and political tensions in Burundi.

Gertrude Kazoviyo and Pékagie Gahungu (2011) “The security sector in Burundi: gradually opening to women.”: A 26-page report carried out by Fride and ITEKA (funded by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs), is among the preeminent texts on gender and SSR in Burundi.

Security Sector Reform Monitor: Burundi (2010): A comprehensive report on SSR in Burundi with a particular focus on the Burundi Armed Forces. This analysis was carried out by The Centre for International Governance Innovation in cooperation with its partners.

If you notice any information that needs to be updated in this SSR Country Snapshot, please let us know at [email protected].

Visit the Centre for

Visit the Centre for