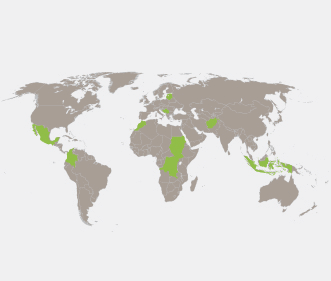

The Centre for Security Governance (CSG) is pleased to announce a new blog series which will discuss the security sector reform (SSR) dimensions of Canada’s planned re-engagement with peacekeeping and peace operations. The main options being speculated upon for troop deployment are the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Mali and South Sudan. This initial article provides background information on the nature of Canada’s strategy for peace and stabilization operations, as well as an analysis of SSR in Mali. Over the next two weeks, the CSG will publish articles highlighting the security governance challenges to address in CAR, DRC and South Sudan.

Introduction

Since coming to office in 2015, Canada’s Liberal Government has made reengaging with peacekeeping a foreign policy priority. This summer, Canada’ Minister of National Defence, Harijat Sajjan, has been pivoting the dialogue from ‘peacekeeping’ as Canadians traditionally know it, to ‘peace support operations’. As Sajjan and colleagues continue to roll out what this entails, the Canadian public and international community await concrete details.

On Friday, August 26, the Canadian Government provided an update on the future of peace support operations. The press conference took a whole-of-government approach, attended by Sajjan and Minister of Foreign Affairs Stephan Dion, Minister of International Development Marie-Claude Bibeau, and Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness of Ralph Goodale.

The press conference came on the heels of Sajjan’s recent five country African study tour to learn more about peace support operations on the continent, including formal peacekeeping operations. The announcement also came two weeks ahead of a major peacekeeping conference in London where Canada hopes to hold some sway.

The four ministers laid out what Canada is willing to provide in the newly announced ‘Peace and Stabilization Operations Program’ or PSOP. PSOP will be managed under Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and commits $450 millions dollars over three years and up to 600 troops and 150 policy officers for deployment. PSOP’s work will focus on conflict prevention, providing security, and mediation. Observers have noted, and the government has acknowledged, that PSOP builds on the successful Stabilization and Reconstruction Taskforce (START) that was formerly housed in the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development and ran for a decade as Canada’s go-to conflict stabilization programming.

What wasn’t announced is where Canada might commit troops. The main options being speculated upon for troop deployment are Mali, the Central African Republic, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. As the first contributor in this mini-series on the security governance dimensions of Canada’s planned re-engagement with peacekeeping, I focus in the next sections on the challenges and context of a Canadian contribution to a peace and stabilization mission in Mali.

The Context of a Peace Support Operation in Mali

To give a brief review of one of the contexts Canada could be stepping into, Mali, bridging West and North Africa, fell into its most recent civil war in 2012. The Tuareg population in the north of the country has had various waves of rebel movements against the government in the south, seeking undelivered development aid, and at times independence. In 2012, a confluence of conditions came together to bring Mali to the brink of collapse including rebel’s access to weapons caches of the deposed Libyan leader Muamar Qaddaffi, corrupt political dealings between various trafficking and terrorist networks that crisscross the Sahel and the Mali government, and a Malian military that had been gutted over years by senior brass unable to take on advancing insurgents. The demoralized soldiers undertook a coup, and the house of cards that Mali was built on was exposed to an international community that had been praising it as a model of democracy for years. French military forces were requested by the Malian government in 2013 to intervene in this deteriorating situation. Driving back Islamic militants in northern Mali, space was left for the government and a coalition of separatist movements, the Coordination des Mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA), to negotiate the Algiers Accord for a peace settlement. The Accord was signed on June 20, 2015, calling for a ceasefire and political reforms.

In 2013, the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) was also established, which currently has over 13,000 military personnel and nearly 2,000 police. MINUSMA and other donors including the European Union, Denmark, and the Netherlands, are carrying out a number of security sector reform programs including technical training for police, building the capacity of the national legislature for security oversight, and developing security sector policies and procedures. Despite this work and the Algiers Accord, MINUSMA, Mali, and remaining French troops continue to work on stabilizing the north and center of the country in the face of escalating violence.

The security governance and SSR dimensions of a peace support operation in Mali

While the press conference was short on specifics on Canada’s approach to peace support operations, some key issues were raised on the approach that will be taken. Sajjan notably placed an emphasis on addressing the root causes of conflict, supporting local innovative initiatives for peace, and ultimately becoming better at conflict prevention.

Taking this initial focus, capacity-building within the security sector is an important dimension of a peace and stabilization strategy. In the context of Mali, this includes supporting locally led dialogue with communities from a human security and not necessarily a counter-terrorism perspective. Residents of northern Mali have expressed frustration that security programs often do not take their concerns into account, including economic and development priorities. A human security perspective would prioritize these concerns as root causes for instability. Additionally, for long-term stability, local communities and create dialogue with security services to increase trust.

Another key dimension would be to find ways to improve security and justice services to create stability. Justice and security provision in Mali, particularly in the north, face a range of challenges including corruption, poor geographic representation, and violations of rights. These deficiencies have led many Malians to seek out informal or traditional forms of justice and security. In terms of security, this has led to recent tensions between an Islamic militant movement attempting to assert itself in the absence of the government, and local militia movements mobilizing in reaction. This would be an area for Canadian police and experts to support capacity building and other donor work, notably the UN Development Program, in establishing community-security dialogue.

Working on security sector oversight to prevent the internal decay of the security forces through corruption is also a key issue to address in Mali to prevent a recurrence of the military’s collapse. In the decade between 2001 and the 2013 coup when France and the US increased military training for Mali, oversight was barely addressed. Thus employing Canada’s 3D approach, support could be provided to ongoing programs building accountability needs to be in internal structures of the Mali military, the Ministry of Defence, and external oversight bodies such as parliament and civil society.

Corruption is of course not self-contained in the security sector. Patronage, embezzlement, and collusion with illicit actors propped up the pre-coup Mali government. Corruption allows criminal and terrorist networks to move not only through Mali, but across West and North Africa. Canada’s peace support operation may not be able to address all the interconnected components of national and regional corruption that undermines security, but a systems mapping of influence networks and travel paths of illicit goods and networks can help identify vulnerabilities. By taking a long-term approach to address this root cause, Canada’s peace support operation could get to Sajjan’s stated goal of working on conflict prevention.

Moving forward: Canada’s potential role and contribution in Mali

The recommendations above are responses to a potential context Canada may find itself involved in Mali, based on the approach that has been outlined by the Canadian Government. To even address these recommendations much more needs to be articulated such as how this approach integrates with MINUSMA, and what personnel with what expertise is Canada willing to deploy, and how will this build on work Canada has contributed to in counter-terrorism capacity building in Mali?

Sajjan made a point of re-emphasizing support to local innovative initiatives to peace during the press conference. While this is a good stance to take, how will these initiatives be supported? Advisors? Direct funding? Will Canada’s funding model be light and flexible to assist and adapt to local complexities?

To get started, the government needs to conduct a mapping of the current context in Mali, what efforts are being undertaken in reform and stabilization by the government, civil society, non-state armed actors and justice providers, and what support international donors are providing to these efforts. Canada does not want to contribute to donor fatigue by overlapping anyone else’s work, or repeating mistakes made. Additionally, Mali has to be examined in the context of it geographic setting and its relations with neighbours, notably regional powers Algeria and Morocco.

As Canada thinks through potential security sector reform programs in Mali, these questions and contextual issues need to be thought through. But stating at the outset that acquiring a deeper understanding of the context of challenges places Canada on a good starting point to engage in Mali.

James Cohen is an expert in international anti-corruption, development, and security with a decade of experience bridging policy and practice. He has written extensively on issues of corruption, security governance, peacekeeping and peacebuilding.

Visit the Centre for

Visit the Centre for